with Katharina Brenner, Luisa Herbst, Destina Atasayar and Lucie Jo Knilli

13.7.2021 – hosted by Lisa Baumgarten and Judith Leijdekkers→ Skip Intro

→ Jump to further resources

→ Download printable PDF-version

→ Learn more about Conversations continued …

[Intro]

Lisa: Thank you so much for taking the time for Teaching Design Conversations continued… We – Judith and I – will give a bit of context on why we are in this space today. I’ll briefly introduce everyone, but we’d like to invite you to introduce yourselves properly before we dive into the conversation.

At the beginning of 2020, we organised a two-week temporary library in Berlin, where we hosted different kinds of conversational formats. We are still drawing from the meaningful encounters and discussions we had during those weeks, which encouraged us to continue the conversations as a way of sharing practices, perspectives and experiences – this time in an online format.

Judith: With Conversations continued..., we reflect on design education through dialogues – as a means to facilitate space for critical reflection and the production of counter-knowledge. We hope to work towards a more collective approach for transforming design practices by focusing on design education. For this project, we bring together educators, students, alumni and staff. We want to include institutionally established education as well as self-organised initiatives and independent practitioners.

Lisa: The dialogue is a format that is embraced in feminist and decolonial discourses. To us, a dialogue – in comparison to e.g. a lecture, a panel discussion or an interview – means giving each other time to speak, taking each other seriously and allowing differences to exist.

Judith: We just want to keep it very casual. It’s not an interview and we would like for it to be also energy-giving and inspiring to all of you.

[Start of Conversation]

Lisa: It is so nice to see you again! I have had the pleasure to meet Katharina, Destina, Jo, and Luisa in the course of their self-organised seminar Eine Krise Bekommen. They invited me as a guest together with my friend and colleague Mara Recklies. Your seminar’s theme really hit a nerve at the time (and still does). When you reached out to us, Mara and I were writing a paper together on design education and care. The conversation we had in your seminar emphasised the importance of care and care structures in teaching and learning spaces. So I already know you a little bit as a group, but it would be lovely if you could introduce yourselves a bit more in depth for Judith and our readers. How about you start, Jo?

Jo: My name is Jo. I study Visual Communication at the University of the Arts Berlin (UdK) and I am currently working on my Bachelor’s thesis. My studies were primarily in the fields of Interaction Design and New Media, but originally I have a Graphic Design background. As a freelancer I primarily work on corporate jobs these days. I try to focus on more meaningful and interesting projects within the university context.

Judith: How about you, Destina?

Destina: Hello, I'm Destina, I study Visual Communications at UdK as well. And spoiler alert: we all do. I experimented with Interaction Design before. Right now I'm focusing on moving images. I'm exploring the medium of film within the topic of migration, focusing on transmigrational perspectives in particular. When it comes to professional work: as a political educator I've been organising workshops for children, young people, teachers and whoever is interested. I’ve been doing that for five or six years now, and it's been really interesting, because each workshop is completely different.

Luisa: I would love to participate in one of your workshops, Destina! I'm Luisa and until now I was mostly working with interventions in public space. It’s a powerful tool for me to question urban developments and their inaccessibilities. Rather than staying in the context of an exclusive art university, I enjoy interacting with people on the streets and collectively claiming these areas. Once we formed up as the student-group Eine Krise bekommen, the topic of discrimination within our art university became more central in my work. I would be glad to take part in more self-organised seminar structures like that.

Lisa: How are you doing, Katharina?

Katharina: Hi, I'm Katharina! I'm currently working on my Bachelor’s thesis, which deals with feminism and design. Besides that, I am part of two student collectives called Klasse Klima and Eine Krise bekommen. The Klasse Klima organises, among other things, a student-led seminar on the climate crisis and campaigns for more climate justice and sustainability in the institution. In recent years, I have also started writing about discrimination at art schools, for example at futuress.org and in our publication Eine Krise bekommen.

Judith: You all met through the programme, right?

Jo: Yes, we all started studying together and some of us kept in touch, and some of us didn't. But we found one another again through a seminar and eventually co-organised the student-led seminar Eine Krise bekommen.

Katharina: The seminars of our theory professor Kathrin Peters are our critical meeting point within the university. Many students interested in topics like inequality and discrimination meet again in these gatherings every semester. The starting point of the student-led seminar we organised – and the publication we made – was a theory seminar of hers called Eine Krise bekommen – Ungleichheit und Diversität. A name we later used for our seminar as well.

Luisa: It's interesting to think about that as a starting point for our process. One year ago in Kathrin Peter’s theory seminar, we all wrote critical texts about problematic consequences of the pandemic, identity struggles and discrimination within art universities. During the process of putting some of them together as a collection of essays, we were confronted with the same moments of pressure and frustration about design ideals like all the years before: clean, minimalistic and structured aesthetics and narratives around always being productive, available and confident were supposed to prepare us students for the profession. Sharing a discomfort about this ideology and discussing this as a group gave us the basis to organise something that allowed us to think and act beyond this reality.

Katharina: While working on the publication during the semester holidays, we experienced a situation where a professor of our programme made fun of us: we were told that we were not working at all and that we were just having a good time. That was a moment where we all got really angry and started talking about our shared experiences of feeling pressured to work and the topic of mental health within the field of design. We realised that we rarely talk about mental health within our institution and we wanted to change that. That was the day we came up with the idea of our own seminar.

Destina: Those conversations that never had space within university structures eventually resulted in us organising ourselves. Back in 2017, at the start of our studies, we were immediately confronted with sexism and dominant, authoritarian teachers. This left us being deeply frustrated. When you start studying, you feel more vulnerable – I just remember trying not to be “weak”, trying to just fit into the art school habitus and behave like everyone else. At some point, we started talking about the issues that were bothering us, things that affected us in our creativity and mental health. But those stories and conversations were never given space in teaching environments. They just happened in-between classes. Unfortunately, it is an experience that many students share.

Lisa: What would you define as “weak”? I think that's very interesting, because I guess most of the people who start studying something artistic have this weird narrative in their heads that specific characteristics or ways of behaving are weak, so maybe we can pinpoint it in some way. Hopefully we can see that what is defined as weak in this context is completely normal, that everybody feels it, and that we’re actually talking about strengths rather than weaknesses.

Destina: I agree! Another part of being “weak” was being seen as weak and internalising that. Being perceived as a young woman who doesn't have her graphic design studio yet – or will never have one – meant receiving way more criticism by teachers. Students who were perceived as men didn’t receive critique as much. Their work was often seen as almost completed. Constantly being questioned makes you ask yourself, “What am I doing? What is my place?” You feel like you're weak. Not being able to endure the night shifts or not constantly having a good idea for your projects. And I mean, we as students probably had great ideas, but these ideas were also devalued if they weren’t presented within the unspoken design codex. That was a recurring experience some fellow students and I had in the first year. Not all professors were judging us like that. But these shared experiences heavily influenced our future studies and self-perceptions.

Luisa: Outside the institution it’s not always obvious that the structures we are studying in are full of unacceptable realities. But when it seems unavoidable to do night shifts before the final presentation in order to reach the teachers’ expectations, it’s clear that only some bodies are capable of doing so. It also produces and normalises a toxic work environment in a university where students quickly become competitors rather than allies.

Jo: Night shifts: that's actually a reality as we speak, because this Friday, everybody has to present their work. As a tutor or someone who is in charge of a workshop you're affected by this: you get texts at 11pm and on weekends from other students who need help and try to get in touch with you. It’s expected that you are pretty much reachable 24/7 during specific times in the semester and if you’re not willing to do that – which I am not – you are often seen as unhelpful. But I'm glad that I'm trying to choose not to be a part of those work habits anymore.

Katharina: These codes, rules and expectations exist subliminally in the institution and are also very present but not spoken out loud, which is very problematic. I think it would be very important to discuss them publicly, because only then we can start questioning and changing them.

Judith: I think it’s remarkable that you recognise these structures while you’re studying. I have had similar experiences during my Bachelor’s at the Delft University of Technology, but at the time, I was not able to put into words why I felt so bad about it. It was only years later that I understood that those experiences were related to structures of oppression. I wonder how that went for you. Did you realise this immediately? And how have you managed to put this into words so quickly? Which experiences led to this realisation?

Katharina: I think we started to critically question our teachers so early on because they were particularly inappropriate. When we entered the room on the first day, the professor leading the foundation year said: “Oh, you're all women and so young! Why didn’t you do something else before your studies?" And so it went on. To be honest, from that moment on I found it very difficult to take this professor seriously. The professor who supervises the foundational programme portrayed our year as particularly bad, as particularly untalented. He did that because we criticised him and stopped attending his classes as a protest. The story that we were “the worst year ever” is still being told to all new students and teachers today. That is so wrong! Our year was full of great people. We just had the courage to criticise his impossible behaviour. In my first year, together with fellow students, I complained about his behaviour to professors, lecturers and the women's representative of our faculty. Unfortunately, our complaint was not followed by any action, but by placating sentences such as “There are much worse candidates." or “You'd better not complain, you'll make life difficult for yourself at the university.” That experience was totally discouraging.

Luisa: Imagine the effect on students of being talked down to only because they voice their criticism right at the beginning of their studies. It didn't create a space where thoughts could be freely exchanged, or a space where you feel comfortable to voice your perspective when you or others have the feeling of not being heard or being treated unfairly. In the beginning, the university didn't seem like a space we could have an influence on. I remember going home frustrated many times and struggling with the impression of, “Is this how studying should be like?” I was also intimidated by all these rumours about facing consequences in the future, if you question this reality openly. Often jobs and scholarships result from close connections between students and teachers and create a financial dependence, so we learned early on that it is risky to voice our critique. This imbalance of power is also perpetuating the untouchable image of the UdK and its professors in general.

Jo: I think we had no choice. And even though I didn't see all of these problematic structures at first – because for one I was quite young starting my studies and not trained to see and question them – but also because I wasn’t as affected by them as a white person with an academic background – there was just no way you could not see and ignore all of that irony. It was just ridiculous: the person selecting us to study here asking us why the majority of us were young women. It took quite some time to get to a point where I could actually verbalise all of this, where I knew how these structures worked and where I could ask for help and to develop strategies for being more vocal about these topics.

Luisa: But in terms of verbalisation, I feel like the framework of our seminar also helped me a lot to find words for my experiences. During the first semesters, the experiences of not being able to meet the norms could feel like an individual problem or individual failure. But a collective exchange adds a bigger picture to it and reveals the hidden structures. For the seminar, we wanted to invite student initiatives and teachers that research design pedagogy and emphasise less toxic working atmospheres. Moving from looking at things from a personal perspective to working out the underlying structures together was helpful to formulate structural criticism, don’t you think?

Destina: Yes, I get what you're saying. Actually a really big process of understanding and critiquing the teaching and the atmosphere at the university really took place while we were working on the book and then planning the seminar. Organising ourselves and also appearing as a group or collective was very empowering and we learnt a lot. The seminar was a valuable experience for me: I started to understand what it means to learn together and how to have a better learning atmosphere, not because we necessarily created the perfect one, but rather because we invited guests that we wanted to learn from. They, as well as the participants, taught us a lot. So I'm deeply grateful for their valuable input.

Katharina: You have mentioned a very important point here, Destina. Performing as a collective or student group was empowering. Suddenly you're no longer critiquing an inappropriate professor on your own, but supporting each other in doing so. Also, as a group with a name, you're taken much more seriously in an institution. It’s astounding, sometimes: as soon as you have a label, you are suddenly perceived as an equal counterpart and invited to events and so on.

Lisa: I recognise this as well. The Teaching Design project started even before I put the platform online. But the moment we had a name, and we had an email signature, it got so much easier to reach out to people. I think understanding yourself as part of something that's bigger than yourself can give you the courage you need in order to act. And not being shy or discouraged. So I think it's an important thing to realise.

Judith: That also counts for the teacher’s perspective. I hear so many teachers – in different surroundings – talking about individuals. About a specific person who is “just really annoying". When one person is complaining, the easiest reaction is to say that this person is just really annoying. When you're complaining collectively, it is not possible anymore to blame a single person for being annoying.

Lisa: Connecting back to what Luisa said before: it's also good to get the perspective of the people who provide the education or facilitate it. To hear from them, like you did with Mara and me when you invited us for a conversation at your seminar. I don't know about the other guests, but I think Mara and I tried to be very transparent about the fact that we are also suffering in this structure. That this is something that is not only oppressive to the students, but also to the teaching staff and the staff working in administration. That we are all in this together and some might come out on top. But in general it's unhealthy on many levels. Could you tell us a bit more about organising the seminar? What were your ideas? How did it go? What were difficulties?

Luisa: It was difficult to get money for the seminar from the university, so we had to write several funding applications. Lisa, I remember our conversation about all the invisible and therefore unpaid work in academic structures. Most of the effort wouldn’t be seen in the final outcome. Also adjunct lecturers aren’t paid for answering students’ emails after the classes or developing and reworking a seminar concept is not part of the official working hours. It was taking most of our time to come up with a framework for the seminar even though some decisions were only visible in detail. What is our common ground and from which perspective are we speaking? What language do we want to use? How do we deal with the hierarchies between students and teachers? How can we build a safer environment for our discussions? Another essential aspect is at least getting credit points for participating in seminars like this, because demanding a shift in our obsolete university systems requires a lot of time and persistence that students in precarious life situations can’t afford to spend.

Katharina: This is also something that really stayed in my head. When planning the seminar, we had very high expectations that this would be a pleasant and healthy seminar. Thinking about alternative ways of teaching and learning naturally took a lot of time and we often got stressed ourselves during the planning. Being stressed for a seminar that is about not being stressed is really contradictory.

Destina: Before we even had an image of what the seminar could look like, we had to apply for it at our university and submitted quite a vague text. We really did not have a concrete plan at the beginning! Perhaps that could be encouraging advice for people who want to organise a seminar. To just do it, and everything else will come. Don't feel insecure about it just because you don't have a solid plan. Maybe you feel like you're not the right person, but you might actually be the right person. We never saw ourselves as teachers but instead thought: “okay, that's great, we have this group and everything else will follow”. So, everyone, if you can, organise yourselves and do your own seminars and lectures!

Katharina: A few weeks before our seminar, we sent out a questionnaire asking all the participants about their needs, wishes and expectations. Most of the students replied to us that they need more room for exchange. These answers were helpful for our seminar planning.

Jo: Within the seminar we primarily wanted to talk about working environments, because unfortunately they are often toxic but we rarely talk about them. A lot of students – and I would definitely not exclude myself from this – think it is super cool to say: “Oh, I don't have time for this and that, I have so much work to do”. Somehow, we normalise “bragging” about how stressed we are. Saying this out loud is sad and depressing. Unfortunately we never really talk about how we actually feel about it. We always try to be tough. And this working atmosphere became even more extreme now with going digital: everybody was doing their own thing and there was hardly any space to talk about our well-being and feelings. These circumstances were especially challenging for new students coming to the faculty, because they don’t know these structures and they have no pre-pandemic comparison they can lean on as a reality check. The reality is that for most of the students, the working environment got even more toxic within the last year and a half.

Katharina: We wanted to give students space to exchange, criticise, and ally. But we also didn't want to stop at criticism. That's why the final task in the seminar was to think together about what possibilities we have for action, including actions that can change unhealthy structures. That's also why we invited teachers that we thought were doing great design teaching. It was really inspiring for us to see that there are people who do better jobs already, and that we can learn something from them and maybe transfer it to our university.

Lisa: So that was your first step. I'm really curious about how you structured the course, specifically. Could you tell us a bit about that?

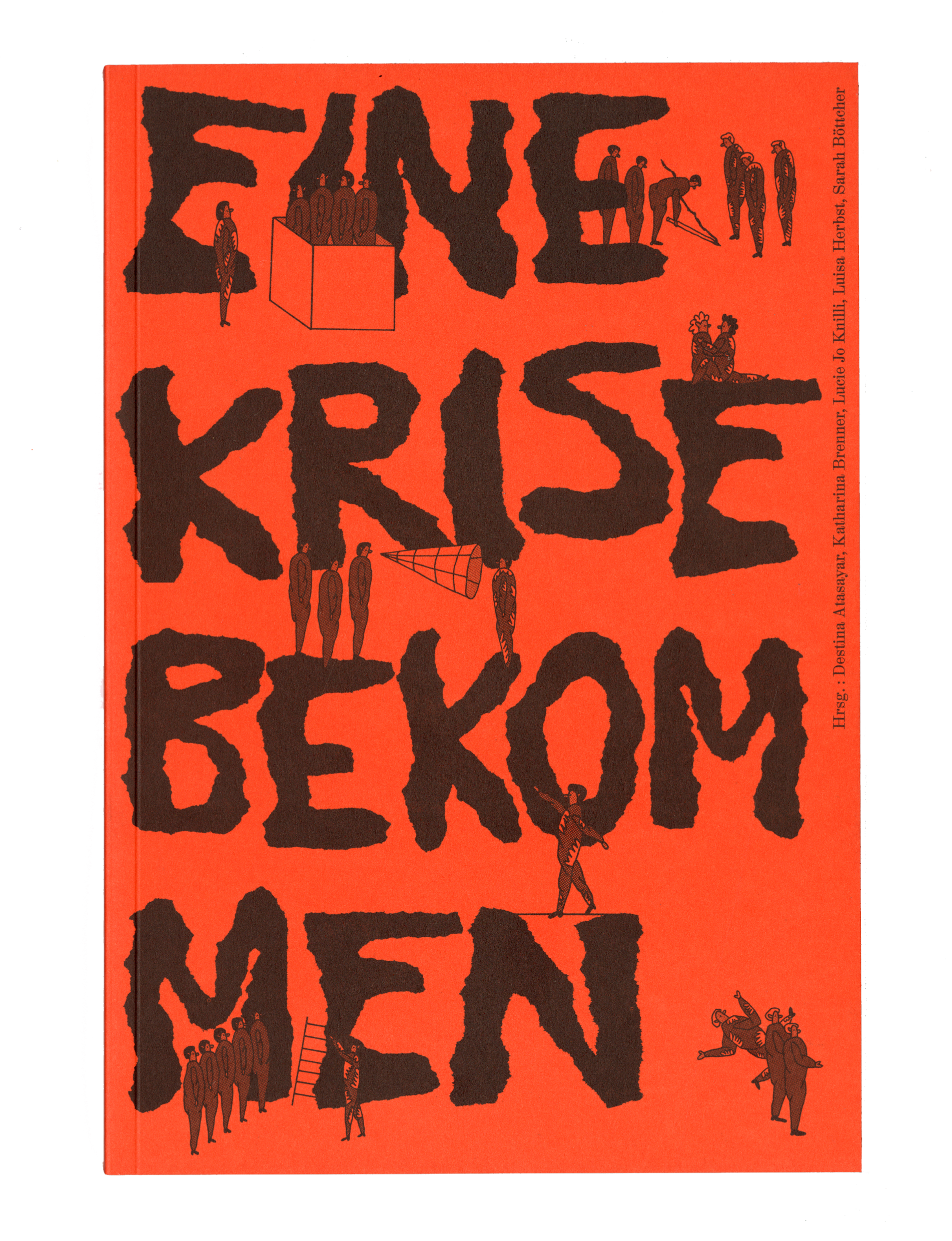

Katharina: Of course, we had a rough plan already. We knew what would be important for us to include, for example, having a lot of breaks and having the seminar in a place that also feels less stressful than a university room. So the seminar took place at the Floating University, a very inspiring, self-organised space next to Tempelhofer Feld. Personally, I found it very pleasant not to discuss the questions we were working on in the university itself, but to be in a place where we had a little distance from it and therefore felt more protected. Even though we had our ideas, it was important to us to also include the needs of the participants and to give them the chance to co-create these spaces with us through the questionnaire. When it comes to how we structured the seminar, we sadly were constrained by the pandemic situation. That’s why we had to do our talks with the guests online. But in the afternoon we could meet in small groups analogously in the Floating University and get to know each other personally. I think that was important to create a familiar atmosphere.

Jo: We had around 120 people applying, which was nice, but alarming at the same time. Unfortunately we didn’t have the capacity to give all these people a chance to participate. Especially since we really wanted to do the seminar in person, which was important to us after having all of these online classes for such a long time. But we also wanted to keep the group small in order to be able to provide a more intimate and safe space. And then there were also the regulations because of the pandemic that forced us to be very flexible, because safety rules were constantly changing.

During our Seminar Eine Krise bekommen: Design und psychische Gesundheit at the Floating University in Berlin. Photo: Katharina Brenner

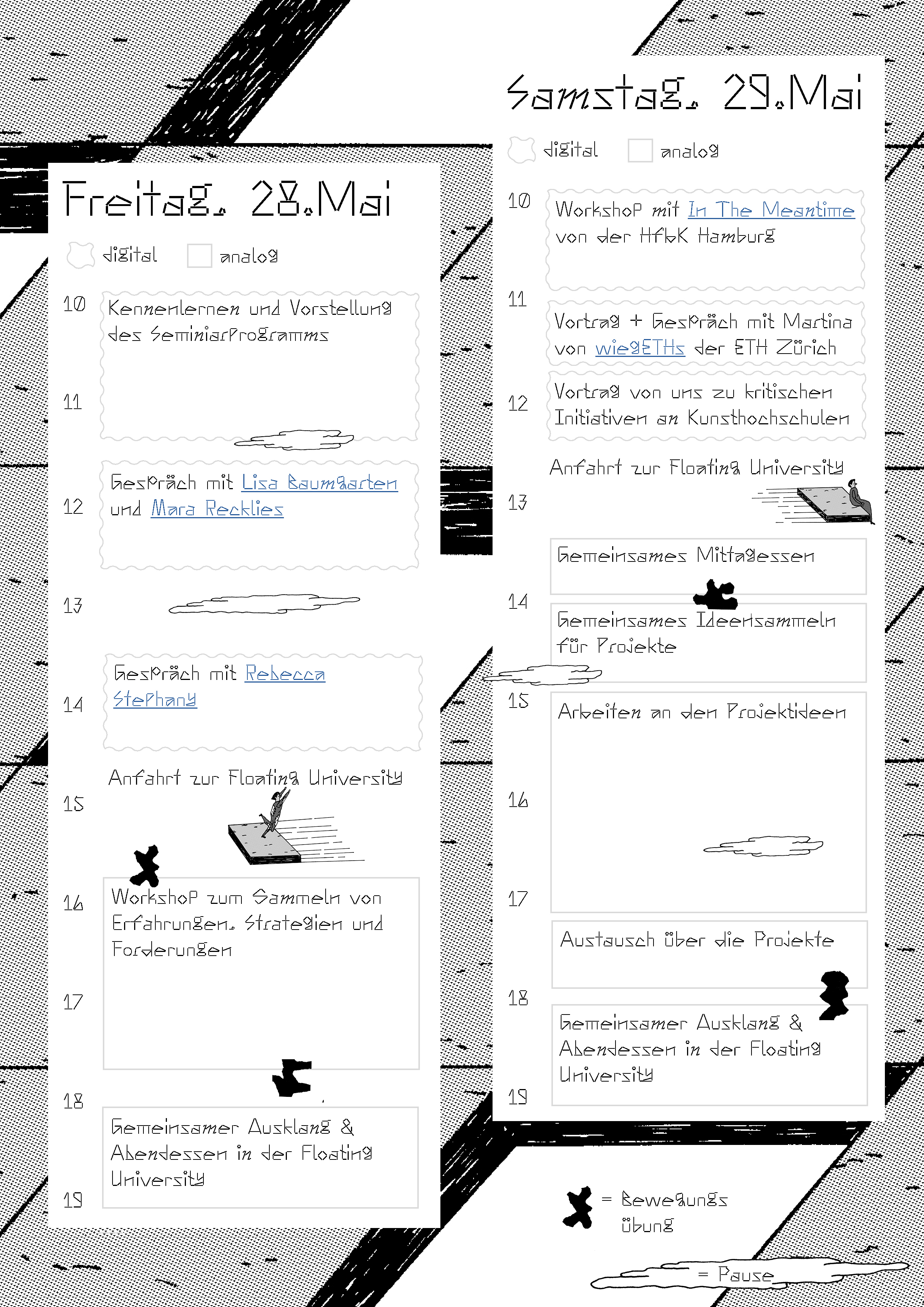

Destina: I especially remember and value our growing list of what we want or need for a safer and more inclusive space. One aspect was our concern about dominant behaviour or talking. We eventually came up with analogue ‘action cards’ to react by holding them into the camera during the online part of the seminar. For those cards we used illustrations by Sarah Böttcher who also worked with us on the publication. We put these cards in an envelope and mailed them to all the participants. I think in the methat made our seminar more interactive.

Katharina: If you, for example, had a question, or you felt uncomfortable, or if you felt like having a break during the seminar, you could just hold one of the action cards into the camera. In digital spaces it's often really hard to grasp how people feel, if someone feels left out or even discriminated against. I found the cards really helpful for this because you could see the reactions of the participants directly. For instance, in our experience, taking breaks is often overlooked in online teaching.

‘Action cards’ illustrated by Sarah Böttcher we used for extended interaction during the online part of the seminar Eine Krise bekommen: Design und psychische Gesundheit.

super like = yes!

palm tree = I need a break.

dialogue = I disagree.

cloud = I don't feel well.

Judith: Did anyone use the “I'm uncomfortable”-card?

Destina: Not that I remember – which does not mean that no one felt uncomfortable. We kept an eye on the cards to see what's happening within the group. However, we did actively try to share the responsibility among the whole group, not only the four of us. At the beginning of the seminar, we talked about how we want to learn together: a group dynamic, where participants can feel encouraged to actively participate or intervene if something goes wrong.

Luisa: Especially asking for feedback if something was going wrong was important to us, we tried to make that clear in the beginning. We hoped that encouraging everybody to interrupt and then see that complaints have an impact would open a space where we look after one another. We invited the participants to not see the seminar as a finished process but more like a format we want to develop together. We also make mistakes. Even though we tried to be as sensitive for discrimination as we could at that point, there are always things that could go wrong. So we tried to allow moments of reflection and shared experiences. It was especially challenging to prepare for conversations about topics concerning mental health or harassment, as it can be a tough situation for people to speak about that. We used trigger warnings and tried to communicate that we have to look out for each other and respect each other’s boundaries.

Destina: In one of our longer emails to the group we mentioned that we would talk about mental health – as a disclaimer. We added that, if the participants notice that the topics are too personal and triggering, it might not be the place for them. We further explained that we cannot get too personal since we are not professionally trained to properly react to certain experiences and our reactions could potentially be triggering. And that we cannot enable a fully safe space. We wrote that we don't know who's going to attend or who might even tell someone else about it. After all, this is still a university context.

Luisa: Instead, we provided information on where and how to get psychological counselling and didn’t avoid addressing these demanding circumstances. Ways to find support are not very accessible at our university, unfortunately. A psychotherapist is offering individual counselling at the UdK from October 2021 onwards, but you can’t find any information on dealing with institutionalised pressure, devaluation and self-doubt in our hallways, even though it fills a lot of our private conversations there. We had a lot of discussions before the seminar started about how we could allow vulnerability and a caring environment but also acknowledge that we are still part of a university context that shouldn’t invade anyone’s privacy. It’s not easy to keep a balance between that.

Jo: Within our seminar we therefore mainly focused on the structural parts of these issues: living in a neoliberal capitalist world with systems designed accordingly. Unfortunately, these circumstances often trigger personal crises. But by analysing these structures it was possible to still give answers without getting into it on a personal level.

Lisa: Yes, I imagine it's a lot of responsibility. So your seminar was a block seminar, right? You met for three days in total. And you said you always had theory in the morning, and then in the afternoon you met to get into action. I would be interested to learn a little bit more about what you mean by “getting into action”. What did that look like?

Jo: We had a lot of ideas – I think we were a bit too excited – which we had to break down quite a bit in the end, because we came to the conclusion that doing less might actually be better. As we could have assumed, in the end everything still went very differently than expected. As mentioned earlier, our goal was to really get active as well. It could be anything from having a conversation with somebody, writing a letter or email, producing a zine, recording a podcast, you name it. But at the same time it was also really important to us to not pressure someone into doing something. To give a little context: it was the end of May and everything was slowly opening up again and therefore it was also possible to meet in bigger groups again. During the seminar we realised that it was a lot more important for the students and us to open up and have discussions and just to talk about experiences instead of working on actual projects. We don't really know yet what kind of projects were actually developed within this seminar, because the final meeting will be this Saturday. We are excited to see what kind of thought processes people went through within the last month or so and what projects might have been developed. But the most important thing is that along the way we met so many lovely people and were also able to connect with other groups throughout this process. For example, we were in touch with a group of students in Hamburg, called In The Meantime, and students from the ETH in Zurich who presented a survey. This helped us realise even more that what's happening is not personal but structural.

The program we developed as guidance for the Seminar Eine Krise bekommen: Design und psychische Gesundheit.

Luisa: One of the participants told us they will start a seminar at the FH Potsdam to initiate a collective reprocessing of the last semesters during the pandemic. They are organising a seminar now called A soft academic revolution where they will rethink public education to create more solidarity and discuss the influence of work performance and productivity on our mental health. It’s clear that there are more and more student-led groups all over Germany that demand change and give this criticism a place within the institutions.

Destina: We were also inspired by In The Meantime, as Jo mentioned before. They organise workshops and were talking with us about creating a comfortable environment and being slower than you expected. They really, really tried to take time for us. It was so inspiring to talk to them! When they joined our seminar at the Floating University, we took flowers and fruits with us and created a music playlist that fitted the mood. We had warm ups and did rubber boot walks through the rainwater basin of the Floating University, talking to one another about individual and collective experiences at art universities.

Jo: Another workshop that took place in the context of our seminar was about developing strategies on how we, as individuals, can help ourselves to cope with specific situations, but also how we can take care of ourselves.

Destina: We set up tables dedicated to different questions where people could sit down and discuss them. The concept was that you could change the tables and rotate on your own time. However, people were staying at one spot and just talked and talked and talked – it took more time than we initially planned. Afterwards, we tried to do a warm-up, to get our bodies moving and to wake up. It didn't work. Some people didn't really want to do it and it was rainy. Not the way we imagined it but that's okay, that's what makes it a workshop and what makes any workshop. You never really know what will happen, which is beautiful.

Katharina: Of course, it is important to have a rough plan for a workshop day, but it is even more important to be flexible with this plan and always take into account the mood and perspectives of the participants. It was also important to us that the outcome could be, for example, a complaint or a conversation with a professor. That a project does not have to look “cool” or “fancy”, but rather stimulates processes or the questioning of structures. We always thought that our seminar needed an output. Probably also because we were used to that from our courses. But what I learnt is that some topics need a lot of space for exchange and that the pressure to produce something can be counterproductive. Sometimes it is more helpful to pause and reflect instead of jumping straight into the next project.

Jo: I think that was something that we didn't really know how to handle. We would be very interested in asking both of you: how do you deal with assignments in your seminars and the pressure to grade the different approaches of your students? Especially when having a seminar within an institution where we are used to working towards credit points. We wanted to resist that pressure, but at the same time I was sometimes also a little disappointed when people didn’t engage the way we expected them to.

Judith: I don't really have seminars with my students. Vocational education is not built around exchange for some weird reason. Students are not taught to do research in the first place. And that means students are not taught or encouraged to ask questions. So when I tell my students that I give the whole class the same pass or fail because we're responsible for each other, that's a really big deal for them, and confusing too. I often tell them that we're not going to do what is in this assignment – because I get assignments on paper and that's what I have to do. I always try to discuss with my students why it is important to sometimes not do what is asked, to question assignments or procedures. I also find it difficult to let go of my own expectations. But by doing so, I allow myself to learn a lot from my students.

Lisa: I have been having many discussions about this. I can relate to the feeling of being frustrated if you organise a seminar and you really put your heart into it and then it seems like some students aren’t really engaging or don't put in the work that you had hoped for. For me, grading and credit points are basically part of oppressive structures in education. Grades enforce a competitiveness that is very unproductive. Credit points are never a display of what a person has learned. I can have someone in the class who is introvert and never says anything, but goes out of my seminar and has an epiphany and will change their design practice. And I won't even know about it. The current system is fostering the environment for a specific personality type. It encourages people who are outspoken, who are very confident, who are competitive, but for everyone who doesn't fit into this template it is a lot harder. So I try not to take it personally when students don't engage, also because I recall that while I was studying, I was doing everything but studying. I was having relationships, being in love and hanging out with my friends and going dancing and maybe doing some design and that was a really important time for me. It was like one of the most important times for me, actually. So I also think that it can be very problematic to be too controlling and to put your expectations and pressure on students. It's also hard because as you said, we grow up in a specific educational context here in Germany. And we have a lot to unlearn – and by “we” I mean both students and teachers. It had to happen a couple of times before I realised that I have to let it go. If I want students to grow up and be self-sufficient, confident and empowered, I also have to give them the responsibility for their own growing up. I think that it can be a way of subverting the system to communicate to students that credit points and grades are not a reflection of their growth and need to be questioned. I think that is actually a really important discussion in the classroom.

Judith: Definitely. I think, in my context, it is the norm for students to not engage, because the curriculum is not at all inspiring or stimulating, and the structure of vocational education is so oppressive. When I first started teaching, I was ready to turn my students into activists. But I got no response, and I realised I was only projecting my ideas and values on my students. In small steps, and by making a lot of mistakes, I learnt how to make space for experiences, knowledges and stories my students brought with them to the classroom. I had to find ways to allow my students to learn from and be responsible for each other. And about grading: it is the norm that the grading takes place right after a class or course, but that means that there is little space to connect the class to real life experiences. I sometimes need weeks, months, or even years to realise what I learnt from a class, a conversation or a text.

Lisa: I think it connects to this idea of knowledge being transmitted by teachers to students. And when it has been fully transmitted, then the students are filled up, and there's nothing more to be learned.

Judith: I do have to say that the fact that I'm showing students I'm not going to do it is really helpful in a weird way. I am working within structures I don’t agree with, but taking the freedom to question these very structures can be very meaningful to both myself and my students. To be a bit naughty, in a way, sometimes disobedient, maybe. Working this way helps me in finding alternatives and sharing these with colleagues.

Katharina: I wanted to add something to what you said about the personality type that is accepted at art schools, Lisa. I once asked my professor: How do you decide who will be part of the study programme? Because it's around 800 people applying and they only take 30 each year. He said to me that they especially look for people who can present themselves and are confident. This made me wonder, because I don't think you need this quality to learn how to design.

Destina: Another “quality” I would like to question or even get rid of is “productivity”! We do have some dinosaurs at university, who are more strict and conservative, and their idea of productivity includes constantly being creative. We just see too many frustrated people coming out of those classes. Why not try to engage with them more and think about different pedagogical ways of teaching? Opening up the room and making it accessible by creating a comfortable and open learning environment. Making your students feel comfortable to talk, not in the sense of oversharing personal details about their lives – which happens way too often at art universities as well – no, just asking the group, creating with the group, and learning from each other. Not taking it personally if someone does not or cannot participate as much. There are always going to be people who are more quiet and reserved or who keep their cameras turned off. As long as you make sure that the person knows how to participate, it should be okay.

Left page:

“only two weeks left until the exhibition. now you really have to dig in!!"

Right page:

“your nail polish goes really well with your outfit today"

This zine with illustrations of dinosaurs and quotes from professors at our university was one of the projects created by students during the seminar Eine Krise bekommen: Design und psychische Gesundheit.

Judith: What makes me really happy in what I see happening between you is that you seem to make sure to have lots of fun with each other. It's inspiring and important to see that working on and discussing topics that are very heavy, can be fun to work on to make sure they bring energy. So I just wanted to say that it shows.

Luisa: That’s nice to hear. We tried to create an atmosphere where we can also say “That’s enough for now, let’s call it a day”. We kept the afternoon hours free for sharing dinner and time together in a non-productive way.

Katharina: We tried to plan the seminar around activities where we could just enjoy our company. During the online sessions for example, we always turned on music during the breaks, which also totally lifted the mood. I think it's quite important when dealing with difficult topics to also make sure you have a good time.

Lisa: I think telling each other you have done a good job is also a way of being disobedient in an institution, which often makes you feel that you're not good enough, right? That can be very powerful. I would say this could be a good time to wrap up. But if you have something that you want to ask or discuss, or maybe something that needs to be said, the space is yours.

Luisa: I have a demand. All the student initiatives around anti-discrimination are doing work that professors and the institutions should cover or that people should be paid for. Actually it’s work that wouldn’t be needed if the academic system would be fair. Of course, it was empowering to experience self-efficacy through being able to agree upon seminar structures and contents ourselves. But still, I assume we could have spent our time with something different than supporting each other after suffering from an exploitative institution. Studying at an art university shouldn’t be “naturally” associated with night shifts and competition, constantly failing to meet a norm that is reserved for few. We need an academic environment that stops creating these false narratives around constant productivity and heroic designers and artists. Professors should take their responsibility and personal influence on their students seriously.

Lisa: I mean, maybe in an ideal world, there wouldn't be professors anymore. So it would be everyone's responsibility to take care of each other like you did in your seminar. So the whole university would be more of a collective. That would be nice.

Destina: I agree a thousand percent. I never understood how pedagogical training is not mandatory at most art universities. Why would you apply for a teaching position, if you are not interested in pedagogy? Where can professors learn how to create learning environments that are not toxic? How to be sensitive for discrimination and power structures? How to deal with it and work against it? How to create a more diverse, inclusive and open knowledge foundation, using sources in their seminars that are not only representing men from Bauhaus? It cannot be only one meeting or training session, it needs to be an ongoing process. And some people are engaging in it, they're opening themselves up and they're teaching, but wow, there's a lot of work to do.

If you are struggling, please know

that help is available and check out

the following resources:

Netherlands:

113 zelfmoordpreventie, https://www.113.nl/

Hulp na seksuele intimidatie en grensoverschrijdend gedrag (Slachtofferhulp), https://www.slachtofferhulp.nl/gebeurtenissen/seksueel-misbruik-geweld/seksuele-intimidatie/

Meldpunt voor ongewenste omgangsvormen in de Nederlandse culturele en creatieve sector (Mores), https://mores.online/

Germany:

Telefonseelsorge, https://www.telefonseelsorge.de/

Hilfe für Opfer von Gewalt,

Weisser Ring , https://weisser-ring.de/

Hilfe für Frauen betroffen von sexualisierter Gewalt,

Wildwasser, http://www.wildwasser-berlin.de/

Further initiatives

that deal with the topics of discrimination, power abuse, and support structures specifically within art and design schools/institutions:Machtmissbrauch

https://www.instagram.com/machtmissbrauch/

In The Meantime

http://www.in-the-meantime.net

Art School Differences

https://blog.zhdk.ch/artschooldifferences/en/

Tools for the times

https://instagram.com/toolsforthetimes

Platform BK

https://instagram.com/platform_bk

cultural.workers.unite

https://www.instagram.com/cultural.workers.unite/

Get in touch with the participants

Eine Krise Bekommen

einekrisebekommen@systemli.org

Editing:

Katharina Brenner, Luisa Herbst, Destina Atasayar,

Lucie Jo Knilli, Judith Leijdekkers and Lisa Baumgarten

Many thanks for proof-reading support

to Sander Holsgens.

Conversations continued… is made possible with the kind support of Stimuleringsfonds